Abramz Tekya started Breakdance Project Uganda in 2006 as a means to empower himself and those around him to initiate social change. Offering free dance classes twice a week, hip-hop is the tool Abramz uses to bring people into the organization, but he aims to do much more than teach people how to dance, "We're a hip-hop organization, but we're not just promoting hip-hop culture. We're using hip-hop culture to empower people to help people. That's why when people come to our program we usually try to help them discover themselves, get to know more about them instead of just being b-boys or b-girls. So we realize we want to be computer literate. People want to be writers, photographers, videographers, but they don't have the opportunity, so when they come to us, as an organization we try to see how we can use our influence or connections to help them get to their dreams. So some people have become computer literate, or get school fees to go back to school, so there's a lot going on."

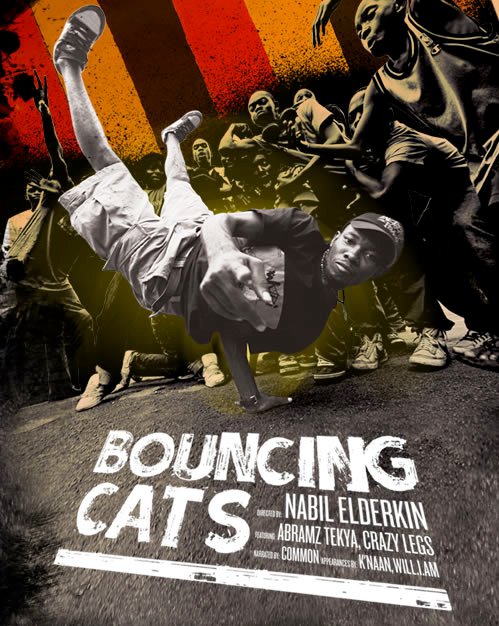

Nabil Elderkin was first introduced to Abramz and BPU through a mutual friend working for OXFAM in Northern Uganda. He was traveling through the region documenting the conflict areas with his camera. Having shot and directed music videos for hip-hop artists such as The Black Eyed Peas, Kanye West, and K'Naan, he was pointed in the direction of Kampala where he met Abramz. He was amazed by what he saw and committed to come back to document the amazing work Abramz was doing. He pitched the idea to Red Bull who eventually produced the film and connected Crazy Legs with the project.

"I've been signed to Red Bull as an athelete for 7-8 years, they presented it to me, it's a trip to Uganda, Africa, there's no money involved and I was like hell yea, I'm down, let's do this. But for me I was into it more for selfish reasons. I'm going to go to the home of the beat, for me that's where breakbeats started," Crazy Legs described what attracted him to the project originally. "I didn't really understand the full scope of what I was about to be involved with, and the depth of the situation over there. It became more of a mission after I came back."

Some of the film's most compelling footage is seeing Crazy Legs and the other members of his crew interact with the members of BPU and discover how much they share. When the founding members of BPU and Rock Steady first meet, Crazy Legs stresses what they have in common, "It's important for you to know, this isn't something that came out of America, this came out of the South Bronx, the South Bronx at that time could have been any third world country, and that's what we have in common, the fact that we all come from shitty conditions, we're born poor. This didn't cost me anything as a child, anything I wanted to do cost money, whether it be boxing, baseball. Any sport we wanted to do cost money, but this...(he starts tapping a beat on a table and bopping his head), and you start doing your thing."

Crazy Legs and his crew then continue on their journey, teaching workshops organized by BPU in Kampala both in a community center auditorium as well as in the middle of Kissini, a slum community of over 30,000 people living without running water or adequate sanitation. The experience visibly affects Crazy Legs as he walks through the streets and sees children walking through mud with bare feet, playing with machetes and sniffing glue to deal with their hunger pains. He comments in the film, "I felt like I was in hell for a second, and it has nothing to do with the people, but the conditions."

While the experience of seeing the most poverty-stricken area in urban Kampala is a powerful experience, traveling to the village of Gulu, in Northern Uganda is even more dramatic. Much of Northern Uganda remains devastated by a civil war where children were abducted and forced to become child soldiers, innocent by-standers had their limbs and/or facial features amputated, and girls as young as 12 or 13 were raped. Abramz bravely travelled to Northern Uganda at a time when no one dared in order to bring BPU to the people of the region as a means of recovery and recuperation for their spirit and to provide a sense of hope.

Director Nabil Elderkin displayed a delicate balance in his selection of graphic images from the Northern conflict area. While he didn't want to alienate any members of his audience, he wanted to show the gravity and reality of the situation, "It's a fine balance with any graphic imagery. I just wanted to show conflict, I wanted to show them this is the reality, this is the situation they've been put through. Without adding extra layers that don't need to be there, it's all about putting it into context, and not exploiting."

It's in Northern Uganda, during a workshop led by Crazy Legs and his crew, that Rocksteady is on the receiving end of a dance lesson. Abramz explains in the film that when he first ventured to Gulu, he would only teach the local kids b-boy moves after they taught him one of their tribal dances. In that tradition, the kids in Crazy Legs' workshop perform their tribal dances for him, and he and his crew become the students.

One of the major themes of the film, is seeing the artform of hip-hop and breakdance come full circle and return to the ancestral source of their creation. While hip-hop culture evolved out of the cultural and socio-economic milieux of mid-1970's South Bronx, the cultural practices ingrained in the Afro-Caribbean and Afro-American values that spawned urban hip-hop culture all trace their lineage back to Africa. Abramz is acutely aware of that lineage and encourages those he teaches to incorporate their traditional African dances into their b-boy moves.

Hip-hop artists such as Mos Def, will.i.am, and K'Naan all comment on the relationship hip-hop has to African culture. Born and raised in Somalia, K'Naan has the most personal insight on the subject matter. He comments in the film, "The songs have a universal feeling of struggle, and hope and overcoming the odds. These are the stories that humanity is made of and for that reason it connects wherever the music is heard."

Nabil Elderkin commented on hip-hop coming full-circle, returning to the source, "I thought it was really beautiful, that's one of the things that inspired me the most about this project, it was seeing something I'm involved with my work in photography and music videos, seeing this music and artform come full circle seeing the place where the beat originated. As K'Naan said in the film, there's poets who have been using drum beats and speaking poetry for thousands of years. I'm sure it was all over Africa, I'm sure the beat has been going on for thousands and thousands of years and somebody was saying something to that beat."

Abramz confirmed Nabil's supposition, "Before I even heard about the word rap, the thing is, people in Uganda had been rapping before we even knew it was the word rap. It was something traditional, it wasn't even urban, it was traditional culture. There were rhymes that people used to recite for the king, and also people in the community, but usually in big ceremonies. They called it ebieontonte. Even the grandparents of our grandparents used to do that. So rap has been around for generations, it's not something that's really new."

Breakdance Project Uganda is currently undertaking a fund-raising effort to build their own community center in Kampala. Crazy Legs and Red Bull are committed to helping BPU raise the necessary funds to build a community center where they can not only teach breakdancing to more kids but also teach kids to use computers, conduct visual art seminars, and lead various other community-building activities. Crazy Legs commented on the process, "Red Bull is doing a great thing. At the end of the day we got involved in something that we realized was much bigger than we expected. And once you become aware, then it's about action. There are many people that are aware, but the awareness without action is useless. Red Bull has made sure that although it's become a different kind of project, they decided to be involved with helping them to establish a website, establish a way to get donations, helping them to get NGO status and things like that. We didn't just go in there document and leave and say hey we did this great film. We documented, we left, and we stayed involved, and I think that relationship is still going to be there at least on my part."

Bouncing Cats is currently touring, screening in different cities and film festivals. To find out about upcoming screenings, donate to Breakdance Project Uganda, or find out more about the project, go to www.BouncingCats.com. This is a powerful film with a story that needs to be told. Go to www.BouncingCats.com to get involved.